November 21, 2016

Do Larger Federal Budget Deficits

Stimulate Spending? Depends on Where the Funding Comes From

The U.S. equity markets have rallied in the wake of

Donald Trump’s presidential election victory. Various explanations have been

given for the stock market rally. President-elect Trump’s pledge to scale back

business regulations are favorable for various industries, especially financial

services and pharmaceuticals. Likewise, President-elect Trump’s vow to increase

military spending is an undeniable plus for defense contractors. But another

explanation given for the post-election stock market rally is that U.S.

economic growth will be stimulated by the almost certain business and personal

tax-rate cuts that will occur in the next year, along with the somewhat less

certain increase in infrastructure spending. It is this conventional –wisdom

notion that tax-rate cuts and/or increased federal government spending

stimulate domestic spending on goods and services that I want to discuss in

this commentary.

Although I have been a recovering Keynesian for decades,

I got hooked on the Keynesian proposition that tax-rate cuts and increased

government spending could stimulate domestic spending after having taken my

first macroeconomics course way back in 19 and 65. I was so intoxicated with

Keynesianism that I made a presentation about it in a political science class.

I dazzled my classmates with explanations of the marginal propensity to consume

and Keynesian multipliers. My conclusion was that economies need not endure

recessions if only policymakers would pursue Keynesian prescriptions with

regard to tax rates and government spending. Reading the body language of my

classmates, I believed that I had just enlisted a new cadre of Keynesians. That

is, until one older student sitting in the back of the class raised his hand

and asked the simple question: Where

does the government get the funds to pay for the increased spending or tax

cuts? I had to call on all of my obfuscational talents to keep my

classmates and me in the Keynesian

camp.

When I graduated from college with a degree in economics,

I still was a Keynesian, perhaps a bit more sophisticated one, but not much. At

graduate school, I became less enchanted with Keynesianism. But Keynesianism is

similar to an incorrect golf grip. If you start out playing golf with an

incorrect grip, you will have a tendency to revert to it on the golf course

even after hours of practicing at the driving range with a correct grip. Bad

habits die hard. So, even though I had drifted away from Keynesianism, it was

easy and “comfortable” to slip back into a Keynesian framework when performing

macroeconomic analysis. Yet, I continued to be haunted by that question my

fellow student asked me: Where does the government get the funds to

pay for the increased spending or tax cuts?

I guess I am a slow learner, but after a number of years

in the “real world”, away from the pressure of academic group-think, I realized

that tracing through the implications of where

the government gets the funds to finance tax-rate cuts and increased spending

is the most important issue in assessing the stimulative effect of changes in

fiscal policy. And my conclusion is that tax-rate cuts and increased government

spending do not have a significant

positive cyclical effect on economic

growth and employment unless the

government receives the funding for such out of “thin air”.

Let’s engage in some thought experiments, beginning with

a net increase in federal government spending, say on infrastructure projects.

Let’s assume that these projects are funded by an increase in government bonds

purchased by households. Let’s further assume that the households increase

their saving in order to purchase

these new government bonds. When households save more, they cut back on their current spending on goods and services, transferring this spending power to

another entity, in this case the federal government. So, the federal government

increases its spending on infrastructure, resulting in increased hiring,

equipment purchases and profits in the infrastructure sector of the economy.

But with households cutting back on their current spending on goods and

services, that is, increasing their saving, spending and hiring in the

non-infrastructure sectors of the economy decline. There is no net increase in spending on

domestically-produced goods and services in the economy as a result of the

bond-financed increase in infrastructure spending. Rather, there is only a redistribution in total spending toward the infrastructure sector and away from other sectors.

What if a pension fund purchases the new bonds issued to

finance the increase in government infrastructure spending? Where does the

pension fund get the money to purchase the new bonds? One way might be from

increased pension contributions. But an increase in pension contributions

implies an increase in saving by the

pension beneficiary. The pension fund is just an intermediary between the

borrower, the government, and the ultimate saver, households or businesses

saving for the benefit of households. Again, there is no net increase in spending on domestically-produced goods and

services in the economy.

What if households or pension funds sell other assets to

nonbank entities to fund their purchases of new government bonds? Ultimately,

some nonbank entity needs to increase its saving to purchase the assets sold by

households and pension funds. Again, there is no net increase in spending on domestically-produced goods and

services in the economy.

What if foreign entities purchase the new government

bonds? Where do these foreign entities get the U.S. dollars to pay for the new

U.S. government bonds? By running a larger trade surplus with the U.S. That is,

foreign entities export more to the U.S. and/or import less from the U.S.,

thereby acquiring more U.S. dollars with which to purchase the new U.S.

government bonds. Hiring and profits

increase in the U.S. infrastructure sector, decrease in the U.S. export or

import-competing sectors.

Now, let’s assume that the new government bonds issued to

fund new government infrastructure spending are purchased by the depository

institution system (commercial banks, S&Ls and credit unions) and the

Federal Reserve. In this case, the funds to purchase the new government bonds

are created, figuratively, out of “thin air”. This implies that no other entity

need cut back on its current spending on goods and services while the

government increases it spending in the infrastructure sector. All else the

same, if an increase in government

infrastructure spending is funded by a net increase in thin-air credit, then

there will be a net increase in spending on domestically-produced goods and

services and a net increase in domestic employment. We cannot conclude that an increase in

government infrastructure spending funded from sources other than thin-air credit will unambiguously result in a net

increase in spending on domestically-produced goods and services and a net

increase in employment.

President-elect Trump’s economic advisers have suggested

that an increase in infrastructure spending could be funded largely by private

entities through some kind of public-private plan. This still would not result

in net increase in U.S. spending on domestically-produced goods and services

and net increase in employment unless

there were a net increase in thin-air credit. The private entities providing

the bulk of financing of the increased infrastructure spending would have to

get the funds either from some entities increasing their saving, that is, by

cutting back on their current spending, or by selling other existing assets

from their portfolios. As explained above, under these circumstances, there

would be no net increase in spending on domestically-produced goods and

services.

Now, it is conceivable that an increase in infrastructure

spending, while not resulting in an immediate

net increase in spending on domestically-produced goods and services, could

result in the economy’s future potential

rate of growth in the production of goods and services. To the degree that

increased infrastructure increases the productivity of labor, for example,

speeds up the delivery of goods and services, then that increase in

infrastructure spending could allow for faster growth in the future production of goods and services.

Another key element in President-elect Trump’s proposed

policies to raise U.S GDP growth is to cut tax rates on households and

businesses. To the degree that tax-rate

cuts result in a redistribution of a given amount of spending away from pure

consumption to the accumulation of physical capital (machinery, et. al.), human capital (education) or

an increased supply of labor, tax-rate cuts might result in an increase in the future potential rate of growth in GDP, but not the immediate rate of growth

unless the tax-rate cuts are financed

by a net increase in thin-air credit.

At least starting with the federal personal income tax-rate

cut of 1964, all personal income tax-rate cuts have been followed with

cumulative net widenings in the federal budget deficits. So, for the sake of

argument, let’s assume that the likely forthcoming personal and business

tax-rate cuts result in a wider federal budget deficit. Suppose that households

in the aggregate use their extra after-tax income to purchase the new bonds the

federal government sells to finance the larger budget deficits resulting from

the tax-rate cuts. The upshot is that there is no net increase in spending on

domestically-produced goods and services nor is there any net increase in

employment emanating from the tax-rate cuts.

My conclusion from the thought experiments discussed

above is that increases in federal government spending and/or cuts in tax rates

have no meaningful positive cyclical

effect on GDP growth unless the

resulting wider budget deficits are financed by a net increase in thin-air

credit, that is a net increase in the sum of credit created by the depository

institution system and credit created by the Fed.

Let’s look at some actual data relating changes in the

federal deficit/surplus to growth in nominal GDP. I have calculated the annual calendar- year federal

deficits/surpluses, and then calculated these deficits/surpluses as a percent

of annual average nominal GDP. The red bars in Chart 1 are the year-to-year

percentage-point changes in the annual budget deficits/surpluses as a percent

of annual-average nominal GDP. The blue line in Chart 1 is the year-to-year

percent change in average annual nominal GDP. According to mainstream Keynesian

theory, a widening in the budget deficit relative to GDP is a “stimulative”

fiscal policy and should be associated with faster nominal GDP growth. A

widening in the budget deficit relative to GDP would be represented by the red

bars in Chart 1 decreasing in magnitude, that is, becoming less positive or

more negative in value. According to

mainstream Keynesian theory, this should be associated with faster nominal GDP

growth, that is, with the blue line in Chart 1 moving up. Thus, according to

mainstream Keynesian theory, there should be a negative correlation between changes in the relative budget

deficit/surplus and growth in nominal GDP. The annual data points in Chart 1

start in 1982 and conclude in 2007. This time span includes the Reagan

administration’s “stimulative” fiscal policies of tax-rate cuts and faster-growth

federal spending, the George H. W. Bush and Clinton administrations’

“restrictive” fiscal policies of tax-rate increases and slower-growth federal

spending and the George H. Bush administration’s “stimulative” fiscal policies

of tax-rate cuts and faster-growth federal spending.

Chart 1

In the top left-hand corner of Chart 1 is a little box

with “r=0.36” within it. This is the correlation coefficient between changes in

fiscal policy and growth in nominal GDP.

If the two series are perfectly correlated, the absolute value of the correlation coefficient, “r”, would be equal

to 1.00. Both series would move in perfect tandem. As mentioned above,

according to mainstream Keynesian theory, there should be a negative correlation between changes in

fiscal policy and growth in nominal GDP. That is, as the red bars decrease in

magnitude, the blue line should rise in value. But the sign of the correlation

coefficient in Chart 1 is, in fact, positive,

not negative as Keynesians

hypothesize. Look, for example, at 1984, when nominal GDP growth (the blue

line) spiked up, but fiscal policy got “tighter”, that is the relative budget

deficit in 1984 got smaller compared to 1983. During the Clinton

administration, budget deficits relative to nominal GDP shrank every calendar

year from 1993 through 1997, turning into progressively higher surpluses relative to nominal GDP

starting in calendar year 1998 through 2000. Yet from 1993 through 2000,

year-to-year growth in nominal GDP was relatively steady holding in a range of

4.9% to 6.5%. Turning to the George H. Bush administration years, there was a

sharp “easing” in fiscal policy in calendar year 2002, with little response in

nominal GDP growth. As fiscal policy “tightened” in subsequent years, nominal

GDP growth picked up – exactly opposite from what mainstream Keynesian theory

would predict.

Of course, there are macroeconomic policies that might be

changing and having an effect on the cyclical behavior of the economy other

than fiscal policy. The most important of these other macroeconomic policies is

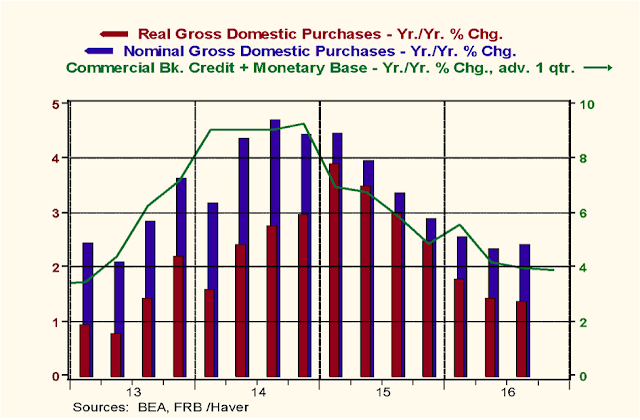

monetary policy, specifically the behavior of thin-air credit. In Chart 2, I

have added an additional series to those in Chart 1 – the year-to-year growth

in the annual average sum of depository institution credit and the monetary

base (reserves at the Fed plus currency in circulation). “Kasrielian” theory

hypothesizes that there should be a positive

correlation between changes in thin-air credit and changes in nominal GDP. With

three variables in chart, Haver Analytics will not calculate the cross

correlations among all the variables. But E-Views will. And the correlation

between annual growth in thin-air credit and nominal GDP from 1982 through 2007

is a positive 0.53. Not only is this correlation coefficient

1-1/2 times larger than that between changes in fiscal policy and nominal GDP

growth, more importantly, this correlation has the theoretically correct sign in front of it. By adding growth in

thin-air credit to the chart, we can see that the strength in nominal GDP

growth in President Reagan’s first term was more likely due to the Fed,

knowingly or unknowingly, allowing thin-air credit to grow rapidly. Similarly,

the reason nominal GDP growth recovered from the George H. W. Bush presidential

years and was relatively steady was not

because tax rates were increased in 1993 and federal spending growth slowed,

but rather because growth in thin-air credit recovered in 1994 and held

relatively steady through 1999.

Chart 2

In sum, there may be rational reasons why the U.S. equity

markets rallied in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidential election victory.

But an expectation of faster U.S. economic growth due to a more “stimulative”

fiscal policy is not one of them unless the larger budget deficits are financed with thin-air credit. Fed

Chairwoman Yellen, whether you know it or not, you are in the driver’s (hot?)

seat.

Paul L. Kasriel

Founder, Econtrarian, LLC

Senior Economic and Investment Advisor

1-920-818-0236

“For most of human history, it has made good adaptive

sense to be fearful and emphasize the negative; any mistake could be fatal”,

Joost Swarte