December 14, 2016

If

You Think the Pace of Economic Activity Is Weak in 2016, Just Wait Until 2017

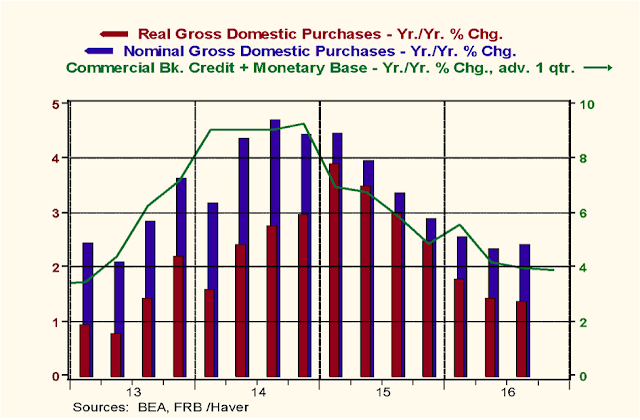

As shown in Chart 1, the year-over-year growth in

real and nominal Gross Domestic Purchases (C+I+G) in Q3:2016 was 1.4% and 2.4%,

respectively. This compares with 2.8% and 4.7% year-over-year growth in real

and nominal Gross Domestic Purchases, respectively, in Q3:2014. So the pace of real and nominal domestic

spending in the four quarters ended Q3:2016 was about half that of the pace in

the four quarters ended Q3:2014. Notice the green line in Chart 1. It

represents the year-over-year percent change in quarterly-average observations

of the sum of commercial bank credit (loans and securities on the books of

commercial banks) and the monetary base (reserves held at the Fed by depository

institutions and currency in circulation). As regular readers (are there still

two of you?) of this commentary remember, this sum is what I refer to as

thin-air credit because it is credit that is created by the commercial banking

system and the Fed figuratively out of thin air. The unique characteristic of

thin-air credit is that no one else need cut back on his/her current spending

as the recipient of this credit increases his/her current spending. Notice that

growth in this measure of thin-air credit, as represented by the green line in

Chart 1, has been trending lower since hitting a post-recession peak in the

fourth quarter of 2014. Growth in thin-air credit is advanced by one quarter in

Chart 1 because my past research has shown that the highest correlation between

growth in thin-air credit and growth in nominal Gross Domestic Purchases is

obtained when growth in thin-air credit leads

growth in nominal Gross Domestic Purchases by one quarter. This suggests, but

by no means proves, that the behavior of thin-air credit has a causal relationship with the behavior of

growth in Gross Domestic Purchases. So,

I believe that the slowdown in the growth of thin-air credit in the past two

years has played a major role in the slowdown in domestic spending during this

period.

Chart 1

Chart 2 provides some insight as to why growth in the sum of commercial

bank credit and the monetary base has been slowing since 2014. The slowdown in

the growth of thin-air credit in the past two years is not because banks have been stingy with their granting of credit.

On the contrary, as can be seen in Chart 2, year-over-year growth in commercial

bank credit (the blue line), after accelerating sharply in 2014, held in a

range of about 6-1/2% to 7-3/4% in 2015 and over the first three quarters of

2016. So, despite the increased regulation that banks are now subject to, bank

credit growth has returned to a rate approximately equal to its long-run

median. No, the culprit has been the Fed. Growth in the monetary base (the

green bars in Chart 2), reserves and currency created by the Fed, decelerated

in 2014. There was essentially no growth in the monetary base in 2015 and there

has been a contraction in it so far in 2016. In 2014, the Fed began to taper

the amount of securities it had been purchasing in the open market in

connection with its third phase of quantitative easing (QE). This resulted in

the deceleration in the growth of the monetary base. In 2015, the Fed ceased

its QE operations. In December 2015, the Fed raised its federal funds rate

target by 25 basis points. In order to “enforce” this higher federal funds

rate, the Fed had to reduce the supply of reserves it created relative to

depository institutions’ demand. This resulted in the contraction in the

monetary base in early 2016. For reasons still a mystery to me, the Fed has

failed to offset the drain of reserves caused by unusually high Treasury

balances at the Fed. In addition, the Fed has been draining reserves from the

financial system via reverse repurchase agreements, presumably to satisfy the

money market mutual funds’ demand for risk-free assets as a result of

regulatory changes that when in effect in October 2016. (See my November 1,

2016 commentary “The Fed Began Tightening Policy in October and No One Knew

It, Maybe Not Even the Fed” for a discussion of this.) This has

resulted in the continued contraction in the monetary base in 2016. In sum, the slowdown in the growth of

combined commercial bank credit and the monetary base in the past two years is

primarily the result of the Fed’s failure to create enough thin-air credit to

prevent the stagnation in monetary base in 2015 and the outright contraction in

the monetary base so far in 2016. And I would submit to you that the

significant deceleration in the growth in combined commercial bank credit and

the monetary base in 2015 and 2016 is primarily responsible for the

deceleration in the growth of both nominal and real Gross Domestic Purchases in

these years as well.

Chart 2

On December 14, 2016, the Fed raised its federal funds rate target by

another 25 basis points. Just as the Fed had to reduce the supply of reserves

relative to depository institutions’ demand for them in order to push the

federal funds rate up to its higher targeted level in December 2015, it will

have to do the same thing in December 2016. This implies a further contraction

in the monetary base. Chart 3 shows the year-over-year annual and three-month

annualized growth in combined commercial bank credit and the monetary base in

the past 12 months. In the 12 months

ended November 2016, growth in combined commercial bank credit and the monetary

base was 2.7%. In the three months ended November 2016, growth in combined

commercial bank credit and the monetary base was a goose egg – that is, zero.

To put the recent growth in this measure of thin-air credit into perspective,

from January 1960 through November 2016, the median year-over-year growth in

monthly observations of combined commercial bank credit and the monetary base

has been 7.1%. So, recent months’ growth in this measure of thin-air credit has

been exceptionally low, both in absolute as well as relative terms. And, with the Fed’s December 14, 2016

decision to raise the federal funds rate another 25 basis points, growth in

combined commercial bank credit and the monetary base will be even weaker in

the coming months.

Chart 3

The extreme weakness in the growth in the past three months of combined

commercial bank credit and the monetary is not

just due to the contraction in the monetary base. As shown in Chart 4, there

also has been some weakening in the growth of commercial bank credit, too. To

wit, in the three months ended November 2016, the annualized growth in

commercial bank credit slowed to 5.6%, the slowest growth since the 5.7% posted

in the three months ended November 2015.

Chart 4

Based on published data so far for Q4:2016, the Atlanta Fed is

forecasting real GDP annualized growth in this current quarter of 2.4%, down

from the previous quarter’s 3.2% annualized growth. With current growth in

thin-air credit already very weak and likely to get even weaker after the Fed

contracts the monetary base more in order to push the federal funds rate 25

basis points higher, real and nominal U.S. economic growth is likely to slow

further in the first half of 2017. Happy Festivus!

Paul L. Kasriel

Founder, Econtrarian, LLC

Senior Economic and Investment Advisor

1-920-818-0236

“For most of human history, it has made good adaptive

sense to be fearful and emphasize the negative; any mistake could be fatal”,

Joost Swarte