January 17, 2017

2017 – Shades of 1937

As a result of some Fed actions taken in 1936 and 1937,

the U.S. economy, after experiencing a robust economic recovery starting in

early 1934, slipped back into a recession midyear 1937, which lasted through

midyear 1938. Based on the recent slowdown in thin-air credit growth, I believe that a significant slowdown in the

growth of nominal and real U.S. domestic demand will commence in the first

quarter of 2017. The duration and magnitude of this slowdown depends on the

future behavior of thin-air credit.

Let’s briefly review the U.S. monetary history of

1936-1938. In response to the robust recovery the U.S. economy was experiencing

and the high level of excess reserves the banking system was maintaining, the

Fed, in a series of steps between August 1936 and May 1937, doubled the percentage of cash reserves

banks were required to hold against

their deposits. The Fed believed that these de

jure excess reserves held by banks were de

facto excess reserves. That is, the Fed did not believe that banks desired

to hold the amount of de jure excess

reserves that were in existence. If these reserves held by banks truly were in

excess of what they wanted to hold, then it was surmised by the Fed that banks

would engage in the creation of new credit for the economy by some multiple of

the existing excess reserves. If this creation of new bank credit were to occur

against a backdrop of an already robust economic expansion, the U.S. economy

would be in danger of overheating. As a

result of this reasoning, the Fed chose to “sterilize” some of these excess

reserves by converting them into required

reserves.

As it turned out, with the experience of bank runs of the

early 1930s still fresh in the memory of bank managers, a large proportion of

the existing excess reserves were, in fact, desired to be held by banks. As a

result, when the Fed decreed that a large portion of these excess reserves

would become required reserves, banks attempted to restore their holdings of

excess reserves. In this attempt, banks contracted

their loans and investments – bank credit. Because only the Fed can

increase or decrease total reserves, this banking system contraction in bank credit did not, in and of itself, increase

total reserves. But what it did do was contract bank deposits, which in turn,

reduced required reserves. For a

given amount of total reserves, a reduction in required reserves implies an

increase in excess reserves. Following the contraction in bank credit and the

sharp slowdown in the growth of bank reserves, the U.S. economy entered a

recession at midyear 1937. In sum, the Fed’s decision back then to double the

reserve requirement ratio against bank deposits set in motion a sharp

deceleration in the growth of thin-air credit that resulted in a U.S.

recession.

Let’s fast forward about 80 years. The Fed has not raised

required reserve ratios. But, as shown in Chart 1, the Fed has begun

contracting an element of thin-air credit, the monetary base (cash reserves

held by depository institutions plus currency in circulation). In 2014, the Fed

began tapering its purchases of securities in the open market, which slowed the

growth in the monetary base. In 2015, the Fed ceased altogether its securities

purchase program and contracted the monetary base at the end of 2015 in order

to push up the federal funds rate by 25 basis points. For reasons still a

mystery to me, the Fed stepped up its contraction in the monetary base in the

second half of 2016, culminating in a further contraction in December 2016 in

order to push up the federal funds rate another 25 basis points.

Chart 1

Another major element of thin-air credit, credit created

by commercial banks, after cruising along at robust growth rates in 2015 and

most of 2016, suddenly decelerated sharply in Q4:2016. I am not aware of any

new regulations or credit-quality concerns that would have motivated commercial

banks to slow their acquisitions of loans and securities. Yes, short-maturity

bank funding rates have crept up in the past two years in response to actual

and expected increases in the federal funds rate. For example, in the week

ended September 30, 2016, the average three-month LIBOR interest rate was 21

basis points higher than it was in the week ended July 1, 2016. If a 21 basis

point increase in bank funding costs caused the quantity demanded of bank credit to slow as much as it did in November and

December 2016, then the interest elasticity of bank credit demand is

extraordinarily high. And if, in fact, the interest sensitivity of bank credit

demand is so high, the Fed might want to take this into consideration in its

federal funds rate targets going forward.

Chart 2

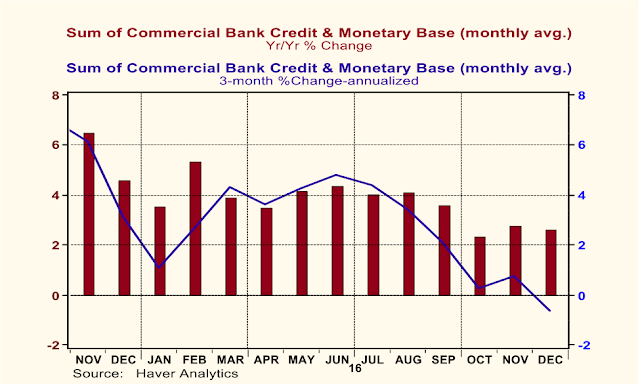

Okay, it is a mystery to me as to why the Fed contracted

the monetary base as much as it did in 2016 and why bank credit growth fell off

a cliff in Q4:2016, but as I amusingly remember hearing in so many corporate staff

meetings – it is what it is. So, let’s combine bank credit with the monetary

base to see what the behavior of this thin-air credit aggregate has been of

late. This is presented in Chart 3. On a year-over-year basis, growth in the

sum of commercial bank credit and the monetary base in December 2016 was 2.6%.

To put this into historical context, from January 1960 through December 2016,

the median year-over-year growth in monthly observations of the sum of

commercial bank credit and the monetary base was 7.1%. In the three months

ended December 2016, the annualized percentage change in this measure of

thin-air credit was minus 0.6%.

Chart 3

So, there has been a deceleration in the growth of this

measure of thin-air credit to a rate that is quite low compared to its longer-run

median rate. So what? Chart 4 provides an answer to this question. Plotted in

Chart 4 are year-over-year percent changes in quarterly observations of nominal

Gross Domestic Purchases and of the sum of commercial bank credit and the

monetary base. The year-over-year percent changes in the sum of commercial bank

credit and the monetary base are advanced by one quarter in order to be

consistent with my hypothesis that the behavior of thin-air credit leads or

“causes” the behavior of nominal Gross Domestic Purchases. Gross Domestic

Purchases are defined as Gross Domestic Product minus exports plus

imports. The correlation coefficient between these two series from Q1:2012

through Q3:2016 is 0.71. If these two series were perfectly correlated, the

correlation coefficient would be 1.00. So, although not a perfect relationship,

there does appear to be a relatively close positive relationship between

changes in this measure of thin-air credit and changes in nominal domestic

purchases of goods and services. With the year-over-year growth in this measure

of thin-air credit slowing from 3.9% in Q3:2016 to 2.6% in Q4:2016 (indicated

by the Q1:2017 blue bar in Chart 4 because growth in thin-air credit is

advanced by one quarter), this augurs poorly for growth in nominal Gross

Domestic Purchases in Q1:2017.

Chart 4

If growth in U.S. domestic demand falters in Q1:2017, as

“predicted” by the recent behavior of thin-air credit, then the Fed is unlikely

to push the federal funds rate higher until it sees a recovery in demand

growth. Even if the Fed holds off on raising the federal funds rate, it still

is unlikely to step up growth in the monetary base component of thin-air credit

in Q1:2017. As mentioned above, I am at a loss to explain the recent sharp

deceleration in bank credit growth. But unless growth in this component of

thin-air credit does re-accelerate, then very weak growth in total thin-air credit

would likely persist through Q1:2017, which would have continued negative

implications for growth in domestic demand for goods and services into Q2:2017.

The Fed’s actions of 1936-37 caused a sharp slowdown in

the growth of thin-air credit, which resulted in the recession of 1937-38. It

is too early for me to forecast a recession in 2017 because of the Fed’s

disregard for the recent growth slowdown in thin-air credit. But I do believe

investor expectations of U.S. economic growth will be disappointed in the first

half of 2017. All else the same, this economic-growth disappointment has

positive implications for U.S. investment grade bonds and negative implications

for risk assets such as U.S. equities.

One factor that could stimulate thin-air credit growth

would be a sharp increase in federal credit demand resulting from tax cuts

and/or discretionary spending increases. This increased credit demand would put

upward pressure on the structure of U.S interest rates. If the Fed were

unwilling to allow the federal funds rate from rising under these

circumstances, then both the monetary base and bank credit would rise in the

face of the increased credit demand. It is not a question of if significant federal tax cuts are

coming in the next two years, but when

and how the Fed will react to them.

Paul L. Kasriel

Founder, Econtrarian, LLC

Senior Economic and Investment Advisor

1-920-818-0236

“For most of human history, it made good adaptive sense to

be fearful and emphasize the negative; any mistake could be fatal”, Joost

Swarte